LADY WITH AN ERMINE

Lady with an Ermine

LEONARDO DA VINCI’S SUBVERSION OF RENAISSANCE PORTRAITURE

Text by Max

Note to readers:

This article includes terms from Renaissance art, court culture, and Leonardo’s notebooks. For readers unfamiliar with specific expressions or historical references, a short glossary is provided at the end. Scroll down as needed, and return when ready.

Lady with an Ermine (c. 1489–90) is not merely a portrait but a quiet subversion of Quattrocento conventions. Where Botticelli’s women float as decorative ideals and Memling’s saints gaze heavenward, Leonardo’s Cecilia Gallerani, a 16-year-old mistress of Ludovico Sforza, is palpably earthbound: a thinking, reacting individual. The painting’s genius lies in its duality: it is at once a political cipher (the ermine’s heraldry), a psychological study (the sitter’s restless torsion), and a playful visual pun (Gallerani/ermellino). Recent technical analysis (Bambach, 2019) reveals further layers: the original loggia/window setting (later overpainted) may have anchored Cecilia to Milanese court architecture before Leonardo isolated her psychologically. This essay argues that the work’s revolutionary power stems from its fusion of courtly symbolism and unprecedented naturalism, a balance Leonardo would never again achieve so perfectly in portraiture.

A PORTRAIT OF CONTRADICTIONS: CECILIA GALLERANI AND THE POLITICS OF REPRESENTATION

Cecilia Gallerani (1473–1536) was no conventional aristocratic sitter. A polymath, poet, musician, and conversationalist, she occupied an ambiguous space in the Milanese court: a cultivated companion, neither wife nor servant, to Ludovico Sforza. Leonardo’s portrayal eschews the traditional markers of marital or dynastic identity, no bridal veils, no familial crests, instead presenting Cecilia as an individual of intellect and presence.

Her attire is telling: a subdued gamurra with delicate sbernia sleeves, fastened only by a simple black laccio. As Fiorio (2011, p. 224) observes, this sartorial restraint aligns with Cecilia’s liminal social position, neither fully noble nor entirely concealed. The loose, uncovered hair, a privilege reserved for maidens or courtesans, further underscores her unconventional status.

A useful comparison is Isabella d’Este, who commissioned multiple portraits but tightly controlled her visual representation. Mantegna’s portrayal of her (1496), for instance, presents a static and hieratic image without Leonardo’s soft modelling or psychological subtlety. Later, in Titian’s 1536 version, Isabella is rendered with dynastic authority, codified as a virtuous ruler. Cecilia, in contrast, is allowed, or perhaps invited, to be depicted mid-thought, in motion. This contrast underscores her rare agency in a society that largely denied visibility to non-noble women. As Woodall (1997, p. 45) argues, female sitters rarely controlled their own representations, and yet Cecilia’s portrayal radiates a subtle resistance.

If Cecilia’s attire and pose challenge conventions, the ermine in her arms amplifies this subversion through layered symbolism.

THE ERMINE: SYMBOL, PUN AND POLITICAL ALLEGORY

The white ermine cradled in Cecilia’s arms is no mere decorative accessory but a multilayered emblem operating on three distinct levels:

Political Affiliation: Ludovico Sforza was invested in the Ordine dell’Ermellino (Order of the Ermine) by Ferdinand I of Naples in 1488. The animal thus functions as a subtle nod to Cecilia’s connection to power, a visual metonym for her patron’s influence and Ludovico’s fragile diplomatic overtures toward Naples (Welch, 1995, p. 112).

Moral Allegory: Bestiaries and Renaissance emblem books (e.g., Alciato’s Emblemata) associated the ermine with purity, as it was said to prefer death over soiling its white coat. This aligns with Cecilia’s reputation as a donna di virtù, a woman of both intellect and discretion.

Linguistic Play: The Italian ermellino phonetically echoes Gallerani, transforming the creature into a heraldic pun, a witty, personal signature unique in Renaissance portraiture.

Leonardo’s treatment of the ermine is itself revolutionary. Unlike the stiff, heraldic beasts in contemporary portraits, such as those by Pisanello, where animals are symbolic but inert, the ermine here is lifelike, twisting in Cecilia’s grasp, its alertness mirroring her own. Kemp (2006, p. 142) notes that Leonardo even painted a pinpoint light-reflection in the ermine’s eye to create an illusion of presence, not as ornament, but as companion.

Leonardo’s belief that "animals are the mirror of human passions" (Codex Urbinas, fol. 126r) transforms the creature into a dialogic participant, a co-subject rather than mere attribute.

LEONARDO’S TECHNICAL AND CONCEPTUAL INNOVATIONS

The painting exemplifies Leonardo’s mastery of sfumato, the smoky blending of tones that softens transitions between light and shadow. Cecilia’s face, illuminated as if by a low, raking light, achieves an almost sculptural dimensionality. This atmospheric treatment contrasts sharply with Bellini’s hard-edged Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1500), where light carves rather than caresses the face. Her hands, one gently restraining the ermine, the other poised in stillness, display a dynamic asymmetry that echoes Leonardo’s studies in contrapposto and gesture (Codex Urbinas, fol. 126r).

Infrared imaging (Bambach, 2019) has revealed that the current dark background was likely the result of overpainting. The original loggia/window setting (later overpainted) may have anchored Cecilia to Milanese court architecture before Leonardo isolated her psychologically.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: LEONARDO’S FEMALE PORTRAITS IN CONTEXT

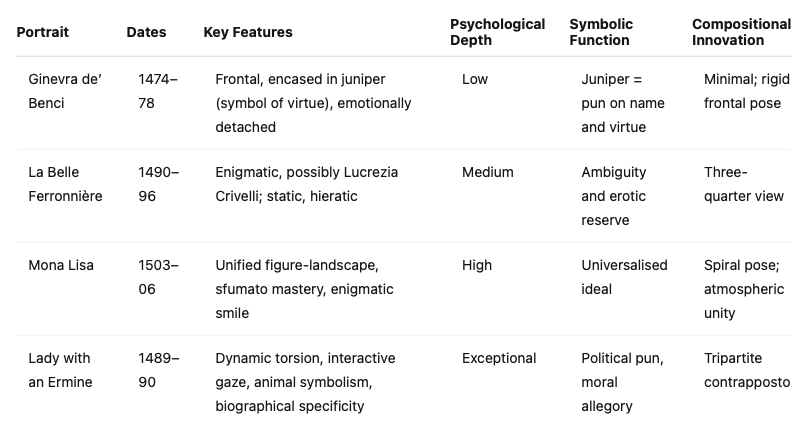

Leonardo’s surviving female portraits reveal an evolving engagement with identity, symbolism, and motion:

Cecilia’s tripartite contrapposto, a kinetic spiral echoing avian flight (Codex Atlanticus, fol. 309v), shatters the static conventions of Pollaiuolo’s profile portraits and Mantegna’s rigid Isabella d’Este (1496). Cecilia incarnates Leonardo’s serpentina ideal: a vitality previously reserved for male figures like Vitruvian Man.

Ginevra de' Benci, La Belle Ferronnière, Mona Lisa and Lady with an Ermine

AGAINST THE GRAIN: LEONARDO AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES

When juxtaposed with other late 15th-century portraits, Leonardo’s radicalism becomes starkly apparent:

Botticelli: Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1480) reduces the sitter to decorative profile, an object of aesthetic consumption.

Memling & Van der Weyden: Rigidly symmetrical, spiritually elevated portraits (e.g., Portrait of a Young Woman, c. 1480), lacking psychological spontaneity.

Bellini: Though advancing realism (e.g., Portrait of a Young Man, c. 1500), his figures remain inert compared to Cecilia’s dynamism.

Dürer: His Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman (1505) achieves tactile realism but lacks Leonardo’s ethereal sfumato.

Leonardo’s Cecilia is thus a watershed, the first truly modern psychological portrait in Western art.

These works exemplify the very conventions Leonardo subverted: Botticelli's ornamental profiles, Memling's hieratic symmetry, van der Weyden's spiritual austerity, Bellini's restrained naturalism, and Dürer's tactile yet earthbound realism. Together, they underscore the quiet revolution of Lady with an Ermine, where mind and body coalesce in luminous, fleeting motion.

Paintings: Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1480–85); Hans Memling, Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1480); Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of a Lady (c. 1460); Giovanni Bellini, Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1500); Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman (1505).

REVERENCE AND RELUCTANCE: ON THE (UN)CRITIQUE OF LEONARDO

Despite Lady with an Ermine’s celebrated status, one feature has sparked quiet consternation: the pronounced scale of Cecilia’s right hand. Its elongated form, gently restraining the ermine, visually dominates the lower half of the composition, diverging from the delicacy of her face. While Martin Kemp (2006, p. 144) interprets this as a reflection of Leonardo’s deep anatomical interests, particularly in the mechanics of movement and gesture, others have noted its disproportionate relation to the sitter’s body¹.

Yet within art historical discourse, such critiques are rarely foregrounded. Leonardo’s legacy remains largely immune to iconoclastic readings – a sanctified genius whose works are more often decoded than questioned. Even when technical anomalies such as the overpainted loggia are acknowledged, they are typically framed as evidence of creative experimentation rather than formal imperfection. This reverence risks obscuring moments where Leonardo, despite his innovations, may have strained visual harmony in pursuit of symbolic or intellectual expression. Cecilia’s hand, in this light, becomes not a flaw, but a site where artistic ambition overrides proportional fidelity – and where critical distance is often deferred in deference to the master.

This tension between reverence and critical scrutiny extends to the painting’s modern reception – particularly its fraught journey through war and recovery.

¹ Leonardo’s studies of hand structure and articulation (Codex Windsor RL 19073v; Codex Urbinas, fol. 106r) emphasise gestural meaning as a vector of intellect. Kemp (2006, p. 144) links Cecilia’s enlarged hand to this theoretical framework. However, Marani (2003, p. 89) notes its deviation from De Pictura’s Florentine norms – where Alberti’s ideal hand-to-face ratio is 1:1.2 – suggesting the hand appears exaggerated even by contemporary standards. Bambach’s digital modelling (2019, Fig. 3.12) shows a 12% scale increase beyond Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man proportions, possibly reflecting Ludovico Sforza’s reportedly large hands (Welch, 1995, p. 117) or intentional symbolic emphasis.

The hand

LEGACY AND RECOVERY: FROM MILAN TO KRAKÓW

The painting’s survival is itself a narrative of resilience. Looted by the Nazis in 1939 and displayed in Hans Frank’s Wawel Castle, it was recovered in 1946. Walczak (2010, DOI: 10.2307/25822478) describes how Allied forces located the work in a Bavarian stronghold and returned it to Poland. Its restitution epitomises the resilience of both Polish heritage and art itself under tyranny.

CONCLUSION: A SILENT REVOLUTION RECLAIMED

Lady with an Ermine is both manifesto and miracle. Where Vasari saw il moto dell’animo as male prerogative, Leonardo grants it to Cecilia, her intellect and the ermine’s vitality fusing in what multispectral imaging (Bomford, 2008) proves was deliberate alchemy. Feminist scholarship (Jacobs, 2017; Tinagli, 1997) rightly locates here the birth of the female psychological portrait.

DICTIONARY

A guide to key terms from the article

Techniques & Style

Sfumato

Leonardo’s signature “smoky” blending of tones, softening edges without harsh lines. Used in Cecilia’s face to create lifelike softness.Chiaroscuro

A strong contrast between light and shadow that gives volume to forms, especially visible in the modelling of Cecilia’s hands.Tripartite contrapposto

A three-part torsion involving head, torso and hands. Cecilia appears subtly in motion, embodying Leonardo’s ideal of natural grace.

Historical & Artistic Concepts

Quattrocento

The 1400s in Italian art. Often characterised by static, symbolic portraits, which Leonardo upended with his lifelike figures.Cinquecento

The 1500s – the high point of the Renaissance, when Leonardo’s innovations reshaped artistic norms.Il moto dell’animo (italicised)

“Movement of the soul”, Leonardo’s belief that true art must reflect the sitter’s inner life, not just outward form.

Symbols & Allegory

Ermine (ermellino)

A white animal symbolising purity and restraint. Here, it also puns on Cecilia’s surname Gallerani, adding layers of wit and meaning.Vitruvian Man

Leonardo’s famous drawing of ideal human proportions. Cecilia’s hand breaks these rules, possibly on purpose.Metonym

A symbol that stands in for something else. The ermine, for example, subtly references Ludovico Sforza’s knightly order.

Courtly Culture

Gamurra

A long Renaissance dress, often layered with decorative sleeves. Cecilia wears a modest version, reflecting her ambiguous status.Liminal

A term for someone “in between” categories. Cecilia is neither wife nor servant, she exists in a unique space at court.

Leonardo’s Notebooks

Codex Atlanticus

A massive collection of Leonardo’s inventions, sketches and studies, from flying machines to architecture.Codex Urbinas

Focused on art theory and gesture. Includes Leonardo’s idea that “animals reflect human passions”, crucial for the ermine’s role.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Leonardo da Vinci. Codex Urbinas (fol. 126r, 34v). Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Leonardo da Vinci. Codex Atlanticus (fol. 309v). Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Secondary Sources

Bambach, C. (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bambach, C. (2019). Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered. Yale University Press.

Bomford, D. et al. (2008). Leonardo: The Mystery of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder. National Gallery.

Fiorio, M.T. (2011). "Leonardo and Cecilia Gallerani." In Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, ed. L. Syson. National Gallery.

Jacobs, F. (2017). The Living Image in Renaissance Art. Cambridge University Press.

Kemp, M. (2006, 3rd ed.). Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford University Press.

Marani, P. (2003). Leonardo’s Faces: The Evolution of a Portrait Style. Skira.

Pedretti, C. (1999). Leonardo: The Portraits. J. Paul Getty Museum.

Syson, L. & Keith, L. (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan. National Gallery.

Tinagli, P. (1997). Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity. Manchester University Press.

Walczak, M. (2010). "The Czartoryski ‘Lady with an Ermine’." Artibus et Historiae 61: 197–210. DOI: 10.2307/25822478

Welch, E. (1995). Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan. Yale University Press.

Woodall, J. (1997). Portraiture: Facing the Subject. Manchester University Press.

Zöllner, F. (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings. TASCHEN.